Authors

Allyson Molzahn, BS1, Merryl Lopido, BS1, Gavin Arnold1, Stella Salmon1, Dave Biffar, MS, CHSOS-A, FSSH1

1Arizona Simulation Technology and Education Center, Health Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding Author

Allyson Molzahn, BS, Arizona Simulation Technology and Education Center, Health Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ

(Email: amolzahn@arizona.edu)

Structured Summary:

Background: Subject matter expert review is a common and crucial part of evaluating new simulation technology; however, there is a lack of consensus guidelines or framework to conduct this review.

Objective: The present study undertakes a scoping review of research on subject matter experts evaluating simulation technology in medical education to investigate common question style, question objectives, number of subject matter experts, and common themes across specialties and modalities.

Design: PubMed was used to identify published papers, from which 171 were selected for data extraction and analysis.

Results: The majority of publications focused on a technology related to a surgical subspecialty and utilized fewer than 20 subject matter experts. The two most common modalities identified were part-task trainers and VR, AR, MR, and screen-based. Most questions for evaluating a new simulation technology focused on assessing realism, with very few addressing the usability of the model.

Conclusions: The process of evaluating new simulation technology with subject matter expert review would benefit from structured guidelines or frameworks. Such guidance can help ensure appropriate methodology aimed at collecting feedback which is actionable and supportive of developing high-quality educational tools in simulation.

Introduction

It is an increasingly common practice in healthcare education to develop new simulation technologies or adapt existing ones for novel educational purposes. These efforts are often driven by the need to address specific training goals for which no suitable tool currently exists, or to modify existing technologies so they better align with a particular learner group or learning objectives. With a newly developed or modified technology, it is best practice to review how well it meets the defined need and its functionality before being implemented with learners. This often takes the form of feedback from subject matter experts. Simulation operations specialists (SOSs), researchers, and educators must decide how to evaluate the technology and when the technology is ready for implementation based on the feedback received.

To our knowledge, there is no widely accepted framework for evaluating simulation technology using subject matter expert (SME) feedback. The Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice for Simulation Design describes general guidelines for evaluation prior to implementation, emphasizing the importance of selecting measures to assess validity, consistency, and reliability, as well as identifying underdeveloped elements (Watts et al., 2021). While this serves as a helpful outline, it does not offer explicit guidance on how to conduct such evaluations in practice.

Several comprehensive frameworks exist for validating simulation technology, including Messick’s validity framework (Joint Committee on the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, 2014), Kane’s validity framework (Cook et al., 2015), and classical validity (Cook & Hatala, 2016) approaches. These frameworks are well-established and extensively documented, offering detailed resources for implementation. However, not all simulation technologies require formal validation. While formal validation is essential for technologies intended for testing or high-stakes assessment, many educational tools do not fall into this category. Given the intensive, multi-step nature of validation and the statistical expertise it demands, it may not be appropriate for early-stage evaluation or for simulations not intended for assessment.

In the absence of a framework, researchers, SOSs, and educators often must rely on non-specific resources to develop evaluation tools. This typically involves referencing general guidelines for survey development (Gehlbach & Artino, 2017; Hill et al., 2022) and searching the literature for SME feedback approaches applicable to their specific simulation technology.

Given the lack of clear guidance, the field of healthcare simulation may benefit from a better understanding of how to conduct SME reviews. While SME input is frequently used to evaluate simulation technologies, there is wide variability in how these reviews are conducted and reported. Inconsistent approaches can limit the utility of feedback. A recent umbrella review of simulation-based education identified a pervasive lack of rigor in methodology, limiting definitive conclusions (Palaganas et al., 2025). To address this gap, a scoping review was conducted to examine how SME reviews have been previously used to evaluate simulation technologies and to identify common practices and methodological patterns. This review aimed to fulfill the following objectives:

- Provide an overview of published evaluations of simulation technology and understand the gaps and inconsistencies in methods.

- Introduce a resource for those involved in simulation operations to use when conducting subject matter expert review.

- Explore how these findings can inform future approaches to simulation technology evaluation.

Methods

The scoping review methodology was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). A full description of the scoping review methodology, including search strategy and inclusion criteria, is available in Supplemental Material 1.

Results

Literature search

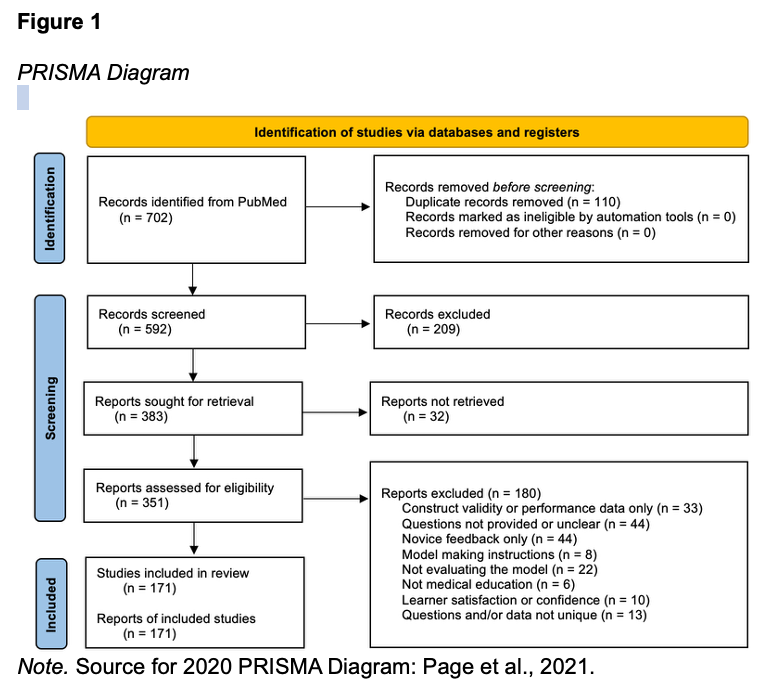

Figure 1 summarizes the data selection and screening process according to PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018). There were 702 records retrieved, of which 171 were identified as eligible and included in this scoping review. The included records are listed in Supplemental Table 1, along with the extracted data: model description, modality, number of experts, primary specialty, sub-specialty, type of participants, question format, and question objective.

Characteristics of included studies

The included studies’ citation, model description, modality, number of subject matter experts, specialty, sub-specialties, participant description and question style are represented in Supplemental Table 1.

Modality

Among the 171 studies included in this scoping review, the most commonly used simulation modality was VR, MR, AR, or screen-based technology (92 studies, 53.8%). Part-task trainers were used in 62 studies (36.3%), while cadaver or live tissue models were reported in 16 studies (9.4%). Only one study (0.6%) used a manikin-based simulator.

Specialty

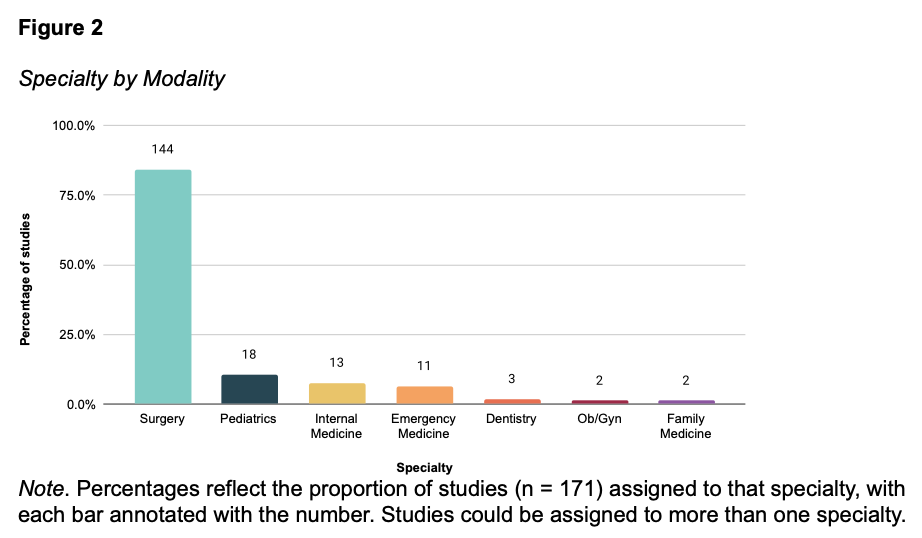

Across simulation modalities, surgery was the most frequently represented specialty overall (84.2%), accounting for 82.3% of part-task trainer studies, 81.3% of cadaver and live tissue studies, 85.9% of VR, AR, MR, and screen-based studies, and the only manikin-based study (Figure 2). Other specialties such as pediatrics, internal medicine, emergency medicine, and dentistry were less represented. Sub-specialties are described in Supplemental Table 1.

Subject matter experts

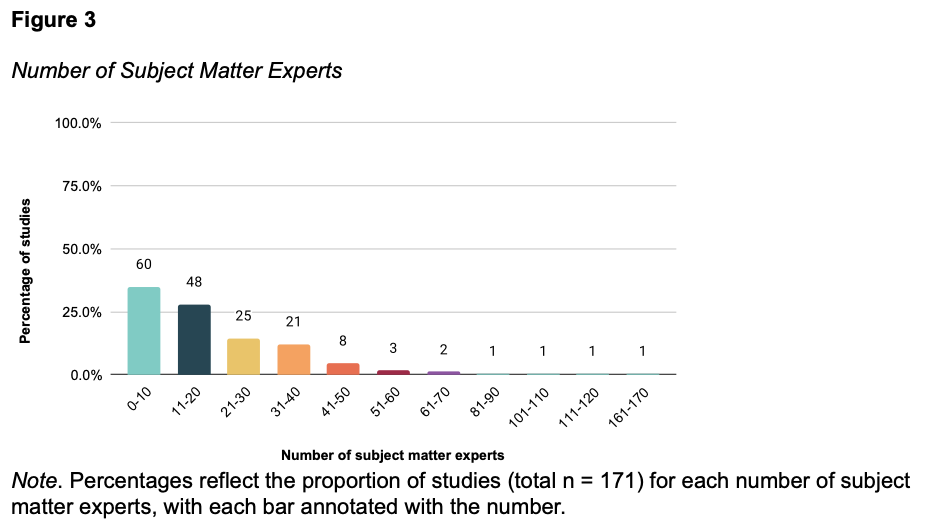

Most studies across all simulation modalities involved a relatively small number of subject matter experts (SMEs), with over one-third (35.1%) including 0-10 SMEs overall (Figure 3). Another 28.1% of studies included 11-20 SMEs, and 14.6% included 21-30 SMEs. Studies with more than 40 SMEs were uncommon, with only a small proportion (under 5%) involving over 50 SMEs. The one manikin-based simulator study had 81-90 participants. A description of the subject matter expert participants for each study can be found in Supplemental Table 1.

Characteristics of included questions

There were 1881 questions extracted from included studies. These questions were categorized based on question format and question objective.

Question format

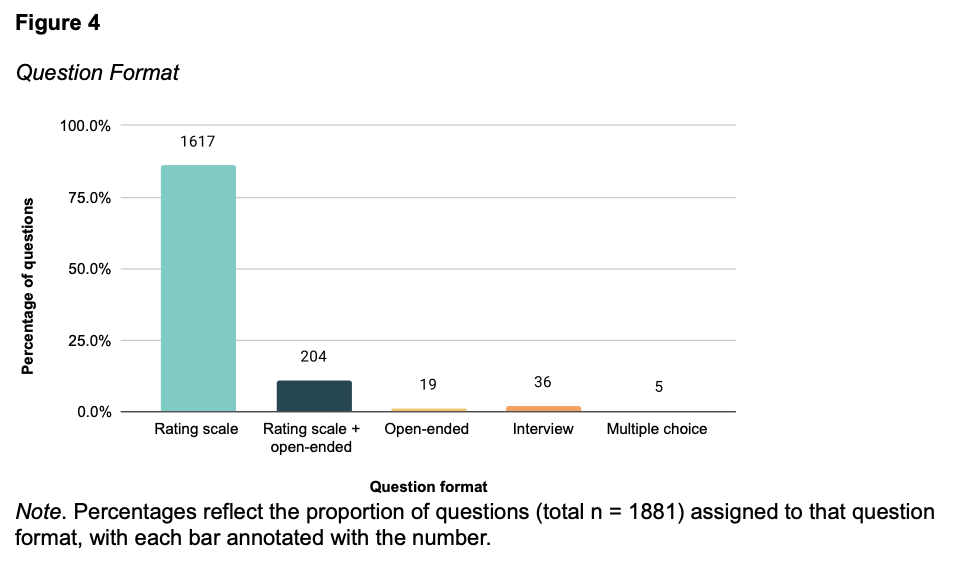

There were 1881 questions categorized based on question format (Figure 4). Across all simulation modalities, most questions (86.0%) used a rating scale format to gather input from subject matter experts. This trend was consistent across all individual modalities: 87.1% of part-task trainer questions, 86.0% of cadaver and live tissue questions, 85.0% of VR, MR, AR and screen-based questions, and 100% of manikin-based simulator questions used rating scales. A smaller proportion of questions used a combination rating scale and open-ended format, accounting for 10.8% of questions overall. Open-ended questions (1.0%), interview formats (1.9%), and multiple-choice questions (0.3%) were all used very infrequently.

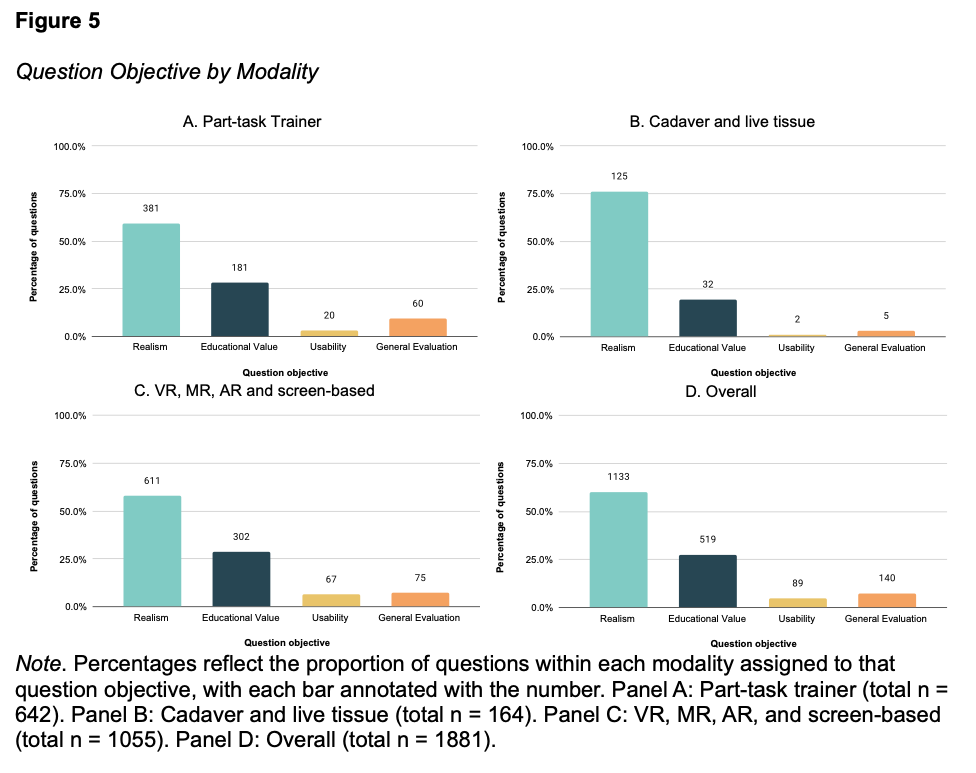

Question objective

There were 1881 questions categorized by question objective (Figure 5). The most common focus was on realism, accounting for 60.2% of all questions. Questions related to educational value made up 27.6% overall. Usability questions were less common, comprising only 4.7% of all questions. These appeared most often in VR, AR, MR, and screen-based studies and were rarely used in other modalities. Of the 20 questions from the mannikin-based simulator study, 16 (80%) were categorized as realism and 4 (20%) were categorized as educational value.

Realism

Of the 1881 questions included in the study, the most common focus was on realism, accounting for 1133 (60.2%) of all questions. For all modalities, realism questions accounted for over 50% of questions asked: 59.3% of part-task trainer questions, 76.2% of cadaver or live tissue questions, 57.9% of VR, AR, MR, and screen-based questions, and 80.0% of manikin-based simulation questions. There were 10 themes related to realism identified across the different modalities that had more than 10 questions (Table 8).

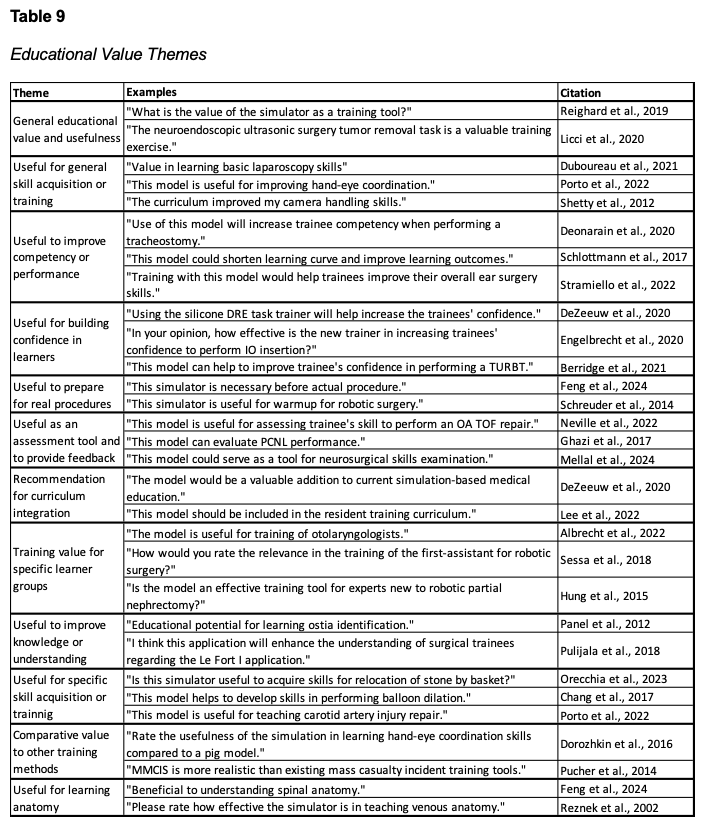

Educational Value

Of the 1881 questions included in this study, there were 519 questions (27.6%) related to educational value. Questions about educational value were evenly represented across modalities, ranging from 19.5% to 28.6% of questions within each group. Across the different modalities, eleven themes related to educational value were identified (Table 9).

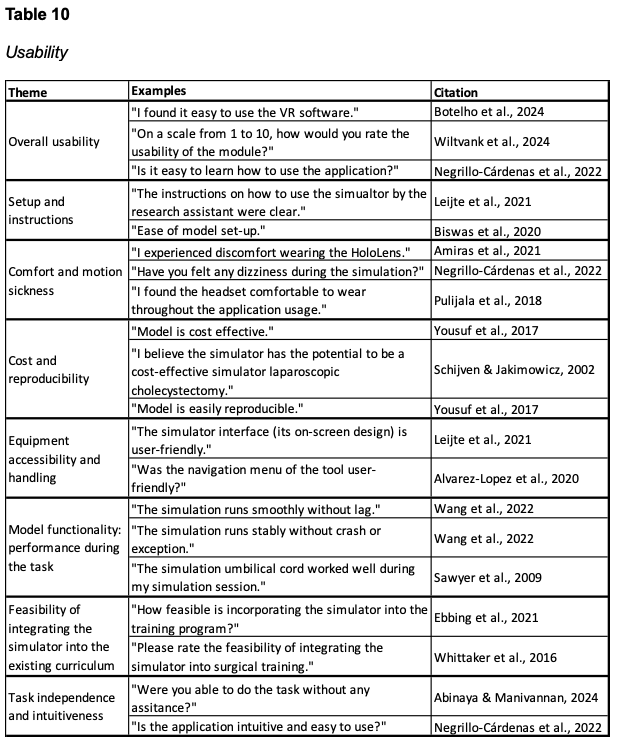

Usability

Of the 1881 questions included in this study, usability questions were least common, comprising only 89 (4.7%) of all questions. These appeared most often in VR, AR, MR, and screen-based studies, accounting for 67 of the 89 usability questions, and were rarely used in other modalities. There were eight themes related to usability identified (Table 10).

Discussion

In this scoping review, we identified 171 studies evaluating simulation technology using subject matter expert feedback. One of our objectives in completing this scoping review was to provide an overview of published evaluations of simulation technology and understand the gaps and inconsistencies in methods.

Simulation Modality

The most prevalent simulation modality identified was VR, MR, AR or screen-based technologies. While this may in part reflect our search strategy, it also aligns with the increasing integration of virtual and mixed reality into medical education (Jiang et al., 2022). The second most common modality was part-task trainers, with very few cadaver or live tissue models and only one manikin-based simulator. This distribution suggests that much of the evaluation activity has centered on technologies for a specific technical skill. Given the growing use of immersive and screen-based simulation technologies, developing frameworks for subject matter evaluation will be increasingly important.

Specialty

Our findings indicate the majority of included studies are conducted on simulation technologies related to surgery. This emphasis likely reflects the challenges surgical trainees face in obtaining hands-on operative experience, which has heightened the importance of procedural simulation (Shahrezaei et al., 2024). The dominance of surgery in this literature underscores the need for a guiding framework to evaluate new technologies. While this focus can also be explained by the inherently procedural nature of surgical training, other procedure-intensive fields such as Emergency Medicine, Ob/Gyn, and Critical Care were less frequently represented and could benefit from developing evaluation approaches to ensure new technologies are high-quality, relevant, and more readily integrated into training. Specialties that are less procedure-intensive, such as Pediatrics, were also underrepresented, with most pediatric studies involving surgical contexts. This highlights an opportunity to expand simulation innovation into non-procedure intensive specialties, supported by subject matter expert review to guide the development and evaluation of new tools.

Subject Matter Experts

Most studies, more than 85%, used 20 or fewer subject matter experts. This is consistent with prior guidance on subject matter expert selection, which emphasizes that for technologies not undergoing formal validation, it is more important to include a representative group of experts than to achieve a larger sample size (Calhoun, 2024). For highly specialized or niche procedures, a smaller but appropriately focused group of SMEs is sufficient, whereas broader, widely applicable technologies warrant input from a larger and more diverse set of experts.

Question Format

To collect feedback, rating scale style questions were overwhelmingly used, with some studies implementing a combination of rating scale and open-ended. Although rating scales provide a structured method for comparing feedback between participants, free response questions allow for deeper insights which may have not been elicited by structured questions. Free response questions also provide an opportunity for SMEs to comment on ways to improve the model to be more clinically accurate. Incorporating both approaches in future evaluations could balance the ease of comparison with the unique perspectives from qualitative responses, enhancing the overall usefulness of SME feedback.

Question Objective

In addition to examining modalities and formats, the studies varied in the objectives their questions addressed, with many focusing on aspects such as realism, educational value, and usability. Questions focused on assessing the realism of the simulation technology most frequently, outnumbering those on educational value and usability. This emphasis may reflect a common belief that establishing a realistic model is the necessary first step before considering educational or usability outcomes. It may also stem from the assumption that realism inherently translates into educational value. However, this is not always true. For example, research has shown that high-fidelity virtual reality simulations, though highly realistic, may overwhelm novice learners with excessive cognitive load (Burkhardt et al., 2025). This underscores the need to look beyond realism and evaluate whether a model meaningfully supports learning.

In contrast, usability was rarely the focus of questions, despite being critical for determining whether a technology can be adopted in a curriculum. One possible explanation is that evaluations of new technologies often prioritize realism and educational value, leaving considerations such as cost, reusability, or ease of setup for later. Another possibility is that developers address these issues earlier in the design process but do not report them when publishing feedback from subject matter experts. Regardless of the reason, overlooking usability in published assessments limits the information available to stakeholders. Even the most realistic or educationally promising technology has little impact if it cannot be implemented practically and sustainably within training programs.

During the process of grouping questions thematically, the authors observed that certain items were difficult to assign to a single group because they lacked contextual detail, combined multiple constructs within a single question, or were ambiguously worded. Although this was not assessed systematically, it is an important consideration, as unclear or compound questions may also present challenges for those responding. This ambiguity in what is being asked can not only make it difficult for experts to determine the construct being evaluated (e.g., visual versus tactile realism) but also reduce the reliability of the responses (Hill et al., 2022). This consideration is key for designing expert questionnaires that yield clear, interpretable, and meaningful data for evaluating new technologies.

Limitations

Our scoping review has some limitations. To make our review more feasible, the review was limited to peer-reviewed publications indexed in PubMed. As a result, studies evaluation simulation technology with SMEs published outside of PubMed-indexed journals may have been excluded. The categorization of questions by objective was subjective, based on the authors interpretation of the question. The authors sought to align our categorization with the definitions provided in the Simulation Dictionary; however, these results may be subject to potential bias (Lioce et al., 2024). In addition, the scoping review methodology does not evaluate the included studies for bias or other quality assessment.

Future Directions

One of our objectives was to create a resource for those involved in simulation operations to use when conducting their own subject matter expert review. Currently, our findings are available in Supplemental Table 1. In the future, we are planning to create a public dashboard with the extracted data to serve as a resource for researchers and simulations operations specialists to guide the design of feedback questions. We also plan to use our findings from this scoping review to inform a more focused and systematic review to critically evaluate the quality of methods and results in the included studies. Because prior evidence shows that engaging subject matter experts and selecting modalities that align with learning objectives enhance the effectiveness of simulation-based education, our work aims to support the development of more rigorous and consistent approaches (Palaganas et al., 2025). Ultimately, these efforts can help lay the groundwork for consensus guidelines or a framework to guide the evaluation of new simulation technologies.

Supplemental Material 1

The detailed methods are available in the online supplemental material for this article at https://docs.google.com/document/d/1sc4yjDpf5o4aD_v7e3kkpx2Ha8wJCjjS8yjNyMrUvN8/edit?usp=sharing

Supplemental Table 1

The included studies are available in the online supplementary table for this article at

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1_n1xex98KwBeemINK0e-LKCmvxWOpm-x1oK3xB6pAbM/edit?usp=sharing

References

Abinaya, P., & Manivannan, M. (2024). Haptic based fundamentals of laparoscopic

surgery simulation for training with objective assessments. Frontiers in Robotics

and AI, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2024.1363952

Albrecht, T., Nikendei, C., & Praetorius, M. (2021). Face, content, and construct validity of a virtual reality otoscopy simulator and applicability to medical training. Otolaryngology, 166(4), 753–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211032897

Alvarez-Lopez, F., Maina, M. F., & Saigí-Rubió, F. (2020). Use of a Low-Cost portable 3D Virtual Reality Gesture-Mediated Simulator for training and learning basic psychomotor skills in minimally Invasive surgery: Development and Content Validity study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(7), e17491. https://doi.org/10.2196/17491

Amiras, D., Hurkxkens, T. J., Figueroa, D., Pratt, P. J., Pitrola, B., Watura, C., Rostampour, S., Shimshon, G. J., & Hamady, M. (2021). Augmented reality simulator for CT-guided interventions. European Radiology, 31(12), 8897–8902. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-021-08043-0

Association, A. E. R., Association, A. P., Education, N. C. O. M. I., & Testing, J. C. O. S. F. E. a. P. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing.

Barsness, K. A., Rooney, D. M., & Davis, L. M. (2013). Collaboration in simulation: The development and initial validation of a novel thoracoscopic neonatal simulator. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 48(6), 1232–1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.015

Berridge, C., Kailavasan, M., Athanasiadis, G., Gkentzis, A., Tassadaq, T., Palit, V., Rai, B., Biyani, C. S., & Nabi, G. (2021). Endoscopic surgical simulation using low-fidelity and virtual reality transurethral resection simulators in urology simulation boot camp course: trainees feedback assessment study. World Journal of Urology, 39(8), 3103–3107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-020-03559-4

Biswas, K., Gupta, S. K., Ganpule, A. P., Patil, A., Sabnis, R. B., & Desai, M. R. (2020). A fruit-tissue (apple) based training model for transurethral resection of prostate: face, content and construct validation. American Journal of Clinical and Experimental Urology, 8(6), 177–184. https://europepmc.org/article/MED/33490306

Botden, S. M., Buzink, S. N., Schijven, M. P., & Jakimowicz, J. J. (2007). Augmented versus Virtual Reality Laparoscopic Simulation: What Is the Difference? World Journal of Surgery, 31(4), 764–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-006-0724-y

Botelho, F., Ashkar, S., Kundu, S., Matthews, T., Guadgano, E., & Poenaru, D. (2024). Virtual Reality for Pediatric Trauma Education - A preliminary face and content validation study. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 161951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2024.161951

Burkhardt, V., Vallette, M., Speck, I., Flayyih, O., Huber, C., Widder, A., Wunderlich, R., Everad, F., Offergeld, C., & Albrecht, T. (2025). Virtual reality cricothyrotomy – a tool in medical emergency education throughout various disciplines. BMC Medical Education, 25(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-06816-5

Calhoun, A. (2024, November 25). A primer on validity and reliability: Best practices [Slide show; Webinar]. Society for Simulation in Healthcare, Assessment Affinity Group.

Chalasani, V., Cool, D. W., Sherebrin, S., Fenster, A., Chin, J., & Izawa, J. I. (2011). Development and validation of a virtual reality transrectal ultrasound guided prostatic biopsy simulator. Canadian Urological Association Journal, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.09159

Chang, D. R., Lin, R. P., Bowe, S., Bunegin, L., Weitzel, E. K., McMains, K. C., Willson, T., & Chen, P. G. (2016). Fabrication and validation of a low-cost, medium-fidelity silicone injection molded endoscopic sinus surgery simulation model. The Laryngoscope, 127(4), 781–786. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26370

Cook, D. A., Brydges, R., Ginsburg, S., & Hatala, R. (2015). A contemporary approach to validity arguments: a practical guide to Kane’s framework. Medical Education, 49(6), 560–575. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12678

Cook, D. A., & Hatala, R. (2016). Validation of educational assessments: a primer for simulation and beyond. Advances in Simulation, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-016-0033-y

Deonarain, A. R., Harrison, R. V., Gordon, K. A., Wolter, N. E., Looi, T., Estrada, M., & Propst, E. J. (2019). Live porcine model for surgical training in tracheostomy and open‐airway surgery. The Laryngoscope, 130(8), 2063–2068. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28309

DeZeeuw, J., O’Regan, N. B., Goudie, C., Organ, M., & Dubrowski, A. (2020). Anatomical 3D-Printed silicone prostate gland models and rectal examination task Trainer for the training of medical residents and undergraduate medical students. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.9020

Dorozhkin, D., Nemani, A., Roberts, K., Ahn, W., Halic, T., Dargar, S., Wang, J., Cao, C. G. L., Sankaranarayanan, G., & De, S. (2016). Face and content validation of a Virtual Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery Trainer (VTESTTM). Surgical Endoscopy, 30(12), 5529–5536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4917-7

Duboureau, H., Renaud-Petel, M., Klein, C., & Haraux, E. (2020). Development and evaluation of a low-cost part-task trainer for laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia in boys and the acquisition of basic laparoscopy skills. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 56(4), 674–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.05.044

Ebbing, J., Wiklund, P. N., Akre, O., Carlsson, S., Olsson, M. J., Höijer, J., Heimer, M., & Collins, J. W. (2020). Development and validation of non‐guided bladder‐neck and neurovascular‐bundle dissection modules of the RobotiX‐Mentor® full‐procedure robotic‐assisted radical prostatectomy virtual reality simulation. International Journal of Medical Robotics and Computer Assisted Surgery, 17(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/rcs.2195

Elisei, R. C., Graur, F., Szold, A., Couți, R., Moldovan, S. C., Moiş, E., Popa, C., Pisla, D., Vaida, C., Tucan, P., & Al-Hajjar, N. (2024). A 3D-Printed, High-Fidelity Pelvis Training Model: Cookbook instructions and first experience. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(21), 6416. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13216416

Engelbrecht, R., Patey, C., Dubrowski, A., & Norman, P. (2020). Development and evaluation of a 3D-Printed adult proximal tibia model for simulation training in intraosseous access. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.12180

Feng, L., Li, W., Lai, J., Yang, W., Wu, S., Liu, J., Ma, R., Lee, S., & Tian, J. (2024). Validity of a novel simulator for Percutaneous Transforaminal endoscopic discectomy. World Neurosurgery, 187, e220–e232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2024.04.070

Ferrarez, C. E., Bertani, R., Batista, D. M. L., Lovato, R., Perret, C., Abi-Aad, K. R., Oliveira, M. M., Cannizzaro, B., Costa, P. H. V., Da Silveira, R. L., Kill, C. M., & Gusmão, S. N. (2020). Superficial Temporal Artery–Middle Cerebral Artery Bypass Ex Vivo Hybrid Simulator: face, content, construct, and Concurrent Validity. World Neurosurgery, 142, e378–e384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.07.027

Gehlbach, H., & Artino, A. R. (2017). The survey Checklist (Manifesto). Academic Medicine, 93(3), 360–366. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002083

Ghazi, A., Campbell, T., Melnyk, R., Feng, C., Andrusco, A., Stone, J., & Erturk, E. (2017). Validation of a Full-Immersion simulation platform for percutaneous nephrolithotomy using Three-Dimensional Printing Technology. Journal of Endourology, 31(12), 1314–1320. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2017.0366

Harrison, P., Raison, N., Abe, T., Watkinson, W., Dar, F., Challacombe, B., Van Der Poel, H., Khan, M. S., Dasgupa, P., & Ahmed, K. (2017). The validation of a novel Robot-Assisted Radical Prostatectomy Virtual Reality Module. Journal of Surgical Education, 75(3), 758–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.005

Hill, J., Ogle, K., Santen, S. A., Gottlieb, M., & Artino, A. R. (2022). Educator’s blueprint: A how‐to guide for survey design. AEM Education and Training, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/aet2.10796

Hsiung, G. E., Schwab, B., O’Brien, E. K., Gause, C. D., Hebal, F., Barsness, K. A., & Rooney, D. M. (2017). Preliminary evaluation of a novel rigid bronchoscopy simulator. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques, 27(7), 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2016.0250

Hung, A. J., Shah, S. H., Dalag, L., Shin, D., & Gill, I. S. (2015). Development and validation of a novel robotic procedure specific simulation platform: Partial nephrectomy. The Journal of Urology, 194(2), 520–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2015.02.2949

Jiang, H., Vimalesvaran, S., Wang, J. K., Lim, K. B., Mogali, S. R., & Car, L. T. (2021). Virtual Reality in Medical Students’ Education: Scoping review. JMIR Medical Education, 8(1), e34860. https://doi.org/10.2196/34860

Johnson, B. A., Timberlake, M., Steinberg, R. L., Kosemund, M., Mueller, B., & Gahan, J. C. (2019a). Design and validation of a Low-Cost, High-Fidelity model for urethrovesical anastomosis in radical prostatectomy. Journal of Endourology, 33(4), 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2018.0871

Johnson, B. A., Timberlake, M., Steinberg, R. L., Kosemund, M., Mueller, B., & Gahan, J. C. (2019b). Design and validation of a Low-Cost, High-Fidelity model for urethrovesical anastomosis in radical prostatectomy. Journal of Endourology, 33(4), 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2018.0871

Lee, W., Kim, Y. H., Hong, S., Rho, T., Kim, Y. H., Dho, Y., Hong, C., & Kong, D. (2022). Development of 3-dimensional printed simulation surgical training models for endoscopic endonasal and transorbital surgery. Frontiers in Oncology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.966051

Leijte, E., Claassen, L., Arts, E., De Blaauw, I., Rosman, C., & Botden, S. M. B. I. (2020). Training benchmarks based on validated composite scores for the RobotiX robot-assisted surgery simulator on basic tasks. Journal of Robotic Surgery, 15(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-020-01080-9

Licci, M., Thieringer, F. M., Guzman, R., & Soleman, J. (2020). Development and validation of a synthetic 3D-printed simulator for training in neuroendoscopic ventricular lesion removal. Neurosurgical FOCUS, 48(3), E18. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.12.focus19841

Lioce, L. (Ed.), Lopreiato, J. (Founding Ed.), Anderson, M., Deutsch, E. S., Downing, D., Robertson, J. M., Diaz, D. A., Spain, A. E. (Assoc. Eds.), & Terminology and Concepts Working Group. (2024). Healthcare simulation dictionary (3rd ed.). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/resources/simulation/terms.html

Mellal, A., González-López, P., Giammattei, L., George, M., Starnoni, D., Cossu, G., Cornelius, J. F., Berhouma, M., Messerer, M., & Daniel, R. T. (2024). Evaluating the impact of a Hand-Crafted 3D-Printed head model and virtual reality in skull base surgery training. Brain and Spine, 5, 104163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bas.2024.104163

Mery, F., Méndez-Orellana, C., Torres, J., Aranda, F., Caro, I., Pesenti, J., Rojas, R., Villanueva, P., & Germano, I. (2021). 3D simulation of aneurysm clipping: Data analysis. Data in Brief, 37, 107258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2021.107258

Moore, J., Whalen, S., Rowe, N., Lee, J., Ordon, M., & Lantz-Powers, A. (2021). A high-fidelity, virtual reality, transurethral resection of bladder tumor simulator: Validation as a tool for training. Canadian Urological Association Journal, 16(4). https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.7285

Nazari, T., Simons, M. P., Zeb, M. H., Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., Lange, J. F., Wiggers, T., & Farley, D. R. (2019). Validity of a low-cost Lichtenstein open inguinal hernia repair simulation model for surgical training. Hernia, 24(4), 895–901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-019-02093-6

Negrillo-Cárdenas, J., Jiménez-Pérez, J., Madeira, J., & Feito, F. R. (2021). A virtual reality simulator for training the surgical reduction of patient-specific supracondylar humerus fractures. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 17(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11548-021-02470-6

Neville, J. J., Chacon, C. S., Haghighi-Osgouei, R., Houghton, N., Bello, F., & Clarke, S. A. (2021). Development and validation of a novel 3D-printed simulation model for open oesophageal atresia and tracheo-oesophageal fistula repair. Pediatric Surgery International, 38(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-021-05007-9

Orecchia, L., Ricci, M., Ippoliti, S., Asimakopoulos, A. D., Rosato, E., Fasano, A., Manfrin, D., Germani, S., Agrò, E. F., Nardi, A., & Miano, R. (2023). External validation of the “Tor Vergata” 3D printed models of the upper urinary tract and stones for High-Fidelity simulation of retrograde intrarenal Surgery. Journal of Endourology, 37(5), 607–614. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2022.0847

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., . . . Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Palaganas, J. C., Mosher, C., Wawersik, D., Eller, S., Kirkpatrick, A. J., Lazarovici, M., Brown, K. M., Stapleton, S., Hughes, P. G., Tarbet, A., Morton, A., Duff, J. P., Gross, I. T., & Sanko, J. (2025). In-Person Healthcare Simulation: An Umbrella Review of the Literature. Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 20(4), 229-239. https://doi.org/10.1097/sih.0000000000000822

Panel, P., Bajka, M., Tohic, A. L., Ghoneimi, A. E., Chis, C., & Cotin, S. (2012). Hysteroscopic placement of tubal sterilization implants: virtual reality simulator training. Surgical Endoscopy, 26(7), 1986–1996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-2139-6

Porto, E., Barbero, J. M. R., Sun, H., Maldonado, J., Rodas, A., DelGaudio, J. M., Henriquez, O. A., Barrow, E., Zada, G., Solares, C. A., Garzon-Muvdi, T., & Pradilla, G. (2022). A Cost-Effective and Reproducible cadaveric training model for internal carotid artery injury management during endoscopic endonasal surgery: the submersible peristaltic pump. World Neurosurgery, 171, e355–e362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2022.12.014

Pucher, P. H., Batrick, N., Taylor, D., Chaudery, M., Cohen, D., & Darzi, A. (2014). Virtual-world hospital simulation for real-world disaster response. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 77(2), 315–321. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000000308

Pulijala, Y., Ma, M., Pears, M., Peebles, D., & Ayoub, A. (2018). An innovative virtual reality training tool for orthognathic surgery. International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 47(9), 1199–1205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2018.01.005

Reighard, C. L., Green, K., Powell, A. R., Rooney, D. M., & Zopf, D. A. (2019). Development of a high fidelity subglottic stenosis simulator for laryngotracheal reconstruction rehearsal using 3D printing. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 124, 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.05.027

Reznek, M. A., Rawn, C. L., & Krummel, T. M. (2002). Evaluation of the educational effectiveness of a virtual reality intravenous insertion simulator. Academic Emergency Medicine, 9(11), 1319–1325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01594.x

Sadovnikova, A., Chuisano, S. A., Ma, K., Grabowski, A., Stanley, K. P., Mitchell, K. B., Eglash, A., Plott, J. S., Zielinski, R. E., & Anderson, O. S. (2020). Development and evaluation of a high-fidelity lactation simulation model for health professional breastfeeding education. International Breastfeeding Journal, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-0254-5

Sawyer, T., Hara, K., Thompson, M. W., Chan, D. S., & Berg, B. (2009). Modification of the Laerdal SimBaby to include an integrated umbilical cannulation task trainer. Simulation in Healthcare the Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 4(3), 174–178. https://doi.org/10.1097/sih.0b013e31817bcaeb

Schijven, M., & Jakimowicz, J. (2002). Face-, expert, and referent validity of the Xitact LS500 Laparoscopy Simulator. Surgical Endoscopy, 16(12), 1764–1770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-001-9229-9

Schlottmann, F., Murty, N. S., & Patti, M. G. (2017). Simulation model for laparoscopic foregut surgery: The University of North Carolina Foregut Model. Journal of Laparoendoscopic & Advanced Surgical Techniques, 27(7), 661–665. https://doi.org/10.1089/lap.2017.0138

Schreuder, H. W. R., Persson, J. E. U., Wolswijk, R. G. H., Ihse, I., Schijven, M. P., & Verheijen, R. H. M. (2014). Validation of a novel virtual reality simulator for robotic surgery. The Scientific World JOURNAL, 2014, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/507076

Sessa, L., Perrenot, C., Xu, S., Hubert, J., Bresler, L., Brunaud, L., & Perez, M. (2017). Face and content validity of XperienceTM Team Trainer: bed-side assistant training simulator for robotic surgery. Updates in Surgery, 70(1), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-017-0509-x

Sethi, A. S., Peine, W. J., Mohammadi, Y., & Sundaram, C. P. (2009). Validation of a novel virtual reality robotic simulator. Journal of Endourology, 23(3), 503–508. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2008.0250

Shahrezaei, A., Sohani, M., Taherkhani, S., & Zarghami, S. Y. (2024). The impact of surgical simulation and training technologies on general surgery education. BMC Medical Education, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06299-w

Shetty, S., Panait, L., Baranoski, J., Dudrick, S. J., Bell, R. L., Roberts, K. E., & Duffy, A. J. (2012). Construct and face validity of a virtual reality–based camera navigation curriculum. Journal of Surgical Research, 177(2), 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2012.05.086

Stramiello, J. A., Wong, S. J., Good, R., Tor, A., Ryan, J., & Carvalho, D. (2022). Validation of a three‐dimensional printed pediatric middle ear model for endoscopic surgery training. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology, 7(6), 2133–2138. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.945

Stunt, J. J., Kerkhoffs, G. M. M. J., Horeman, T., Van Dijk, C. N., & Tuijthof, G. J. M. (2014). Validation of the PASSPORT V2 training environment for arthroscopic skills. Knee Surgery Sports Traumatology Arthroscopy, 24(6), 2038–2045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-014-3213-0

Takahashi, S., Ozawa, Y., Nagasawa, J., Ito, Y., Ouchi, G., Kabbur, P., Moritoki, Y., & Berg, B. W. (2019). Umbilical catheterization training: Tissue hybrid versus synthetic trainer. Pediatrics International, 61(7), 664–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.13904

Timberlake, M. D., Garbens, A., Schlomer, B. J., Kavoussi, N. L., Kern, A. J., Peters, C. A., & Gahan, J. C. (2020). Design and validation of a low-cost, high-fidelity model for robotic pyeloplasty simulation training. Journal of Pediatric Urology, 16(3), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.02.003

Torkington, J., Smith, S. G., Rees, B. I., & Darzi, A. (2000). The role of simulation in surgical training. PubMed, 82(2), 88–94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10743423

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., Lewin, S., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of internal medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Wang, H., & Wu, J. (2022). A time-dependent offset field approach to simulating realistic interactions between beating hearts and surgical devices in virtual interventional radiology. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1004968

Watts, P. I., McDermott, D. S., Alinier, G., Charnetski, M., Ludlow, J., Horsley, E., Meakim, C., & Nawathe, P. A. (2021). Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 58, P14-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2021.08.009

Weinstock, P., Rehder, R., Prabhu, S. P., Forbes, P. W., Roussin, C. J., & Cohen, A. R. (2017). Creation of a novel simulator for minimally invasive neurosurgery: fusion of 3D printing and special effects. Journal of Neurosurgery Pediatrics, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.1.peds16568

Whittaker, G., Aydin, A., Raison, N., Kum, F., Challacombe, B., Khan, M. S., Dasgupta, P., & Ahmed, K. (2015). Validation of the RobotiX Mentor Robotic Surgery Simulator. Journal of Endourology, 30(3), 338–346. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2015.0620

Wiltvank, I. L., Besselaar, L. M., Van Goor, H., & Tan, E. C. T. H. (2024). Redesign of a virtual reality basic life support module for medical training – a feasibility study. BMC Emergency Medicine, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-024-01092-w

Yousuf, A. A., Frecker, H., Satkunaratnam, A., & Shore, E. M. (2017). The development of a retroperitoneal dissection model. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(4), 483.e1-483.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.07.004