Authors

Brian F. Quach BS1, Eric Nohelty BS, CHSOS2,3, Andrew J. Eyre MD, MS2,3,4

1Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine at Quinnipiac University, North Haven, CT

2STRATUS Center for Medical Simulation, Boston, MA

3Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Department of Emergency Medicine, Boston, MA

4Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest. Innovations were designed at the STRATUS Center for Medical Simulation when author BFQ was employed there.

Corresponding Author

Brian F. Quach, BS, Frank H. Netter MD School of Medicine at Quinnipiac University, North Haven, CT

(Email: Brian.Quach23@gmail.com)

Brief Description

Type I and type II diabetes are major metabolic disorders that affect over 500 million adults worldwide and are responsible for 3.4 million deaths worldwide (IDF Diabetes Atlas, 2025). Diabetic emergencies related to poor glycemic control constitute a significant proportion of annual emergency room visits, with no indication of a decline in frequency in the near future (McDermott et al., 2022; Uppal et al., 2022). Neuropathy and vasculopathy place patients with diabetes at increased risk for foot ulcers and wound infections. When present, these infections can cause significant morbidity such as chronic non-healing wounds, osteomyelitis, amputations and systemic infections (Frazee, 2024; Jeyaraman et al., 2019; Jupiter et al., 2015). Wound debridement and comprehensive wound care can be utilized to minimize the risk of infection. Medical simulation provides an opportunity to teach clinicians how to properly care for diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) in addition to developing the psychomotor skills required for wound debridement. To help address current limitations surrounding accessibility to DFU simulators, we propose a preliminary design for a DFU trainer that is easily made, reproducible, dynamic, and cost-effective.

Introduction

Diabetes is a chronic illness that occurs when the body is unable to regulate blood glucose levels appropriately. This condition manifests in two variations, when the body does not produce enough insulin (Type I) or is unresponsive to the secretion of insulin (Type II) (Ozougwu et al., 2013; Rawshani et al., 2017). Diabetes and prediabetic risk factors have been deemed a rising public health issue worldwide (Management-Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment, 2016; Diabetes Statistics, 2025). Diabetic neuropathy, a complication of uncontrolled diabetes, refers to nerve damage that commonly causes loss of sensation in the feet (Bansal et al., 2006; Feldman et al., 2019). Diabetic neuropathy contributes to the development of foot ulcers, chronic wounds, and acute infections that can significantly alter a patient’s quality of life if not cared for properly (Bader, 2008; Jeffcoate & Harding, 2003; Snyder & Hanft, 2009). Up to one-third of individuals with diabetes worldwide will develop a foot ulcer, with a lifetime risk estimated between 19% and 34%. After healing of an initial ulcer, the risk of recurrence is even higher (Edmonds et al., 2021).

Proper wound dressing and surgical debridement are treatment modalities which minimize the risk of further tissue infection and damage (Lebrun et al., 2010; Moura et al., 2013). However, developing the proper technique for these modalities may be difficult for novice clinicians. Medical simulation training offers a psychologically safe and educationally enriching experience for clinicians and students to practice psychomotor skills under the guidance of senior practitioners. As of August 2024, there are a limited number of commercial wound debridement simulators that are surgically interactive and available for purchase. This prompted the creation of a preliminary design for a simulated foot trainer with diabetic skin ulcers using repurposed materials available in our simulation lab. The following model design methods will provide basic and reproducible instruction on how to design a simulator that can be customized for foot wound dressing and debridement training. As DFU wound debridement is often performed using sharp instruments like a scalpel or a curette, we prioritized operator safety when conceptualizing the design for this trainer to minimize the risk of unintentional injuries. This necessitated utilizing a rigid material for structural integrity of the foot and strategic placement of ulcerated skin pads to prevent hand crossover during debridement. In our case, a silicone foot was used for the construction of our simulator.

Objective

As diabetes is becoming more prevalent, podiatric interventions may become an increasingly important component in caring for patients with diabetes (Saeedi et al., 2019). However, as there is a limitation in the number of surgically interactive DFU trainers available for purchase, the introduction of more interactive simulators could enrich podiatric training opportunities. Our objective was to create a low-cost, dynamic, and easily made task trainer for high quality diabetic podiatric care. As this is a preliminary design, we hope the methods used to create this model can serve as a foundation for the development of more advanced task trainers in the improvement of podiatric care (Grollo et al., 2018).

Methods

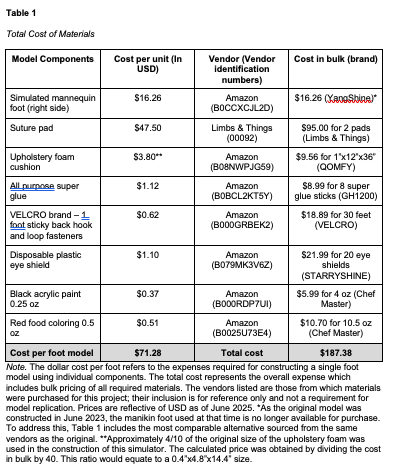

The cost and materials to create the simulated diabetic foot ulcer are presented below (Table 1).

The anatomical location and size of DFUs vary widely between individuals. This preliminary model includes plantar ulcerations in weightbearing areas such as the heel and medial first metatarsal, along with dorsal wounds over the fourth and fifth metatarsals (LeMaster et al., 2008; Ünlü et al., 2007). Simulated ulcerations and wound beds, which served as the debridable regions of the task trainer, were created using commercially available suture pads (Limbs & Things, Bristol, England, United Kingdom). We developed a podiatric task trainer for the management of diabetic foot ulceration (Appendices A – D). The stepwise methods below illustrate the design process behind the model, starting with the construction of simulated ulcerations then progressing to the construction of the foot.

Select and mark locations for ulcer placement on foot.

Use a #1 blade scalpel, excise skin from foot. Ensure the area being cut is sized appropriately for the introduction of simulated ulcerations.

Cut suture pads to match section removed from the foot.

Make incisions 2 cm deep into the suture pads on the skin side and expand circumferentially to create an adequately sized wound bed.

Stain the subcutaneous fat layer with red food coloring to simulate the appearance of healthy wound bed tissue.

Apply super glue and dirt over the healthy wound bed to simulate a necrotic ulcer for debridement.

Apply hook and loop fastener to the bottom of the suture pad for insertion into foot model.

Place upholstery foam into the section removed the foot. If the simulated foot is hollow, add upholstery foam to provide structural integrity and resistance. Alternative materials include silicone rubber, plastic inserts, and memory foam. For solid models, this step may not be required.

Cut a single pair of disposable plastic eye shields into rectangular segments and size appropriately to fit within the resected regions. Alternative materials include any durable plastic such as acrylic or polyethylene terephthalate from plastic water bottles. The addition of this plastic layer is essential for the mounting of the simulated ulcerations.

Apply super glue between the upholstery foam and the plastic pieces until adequately adhered.

Place strips of hook and loop fastener onto the exterior aspect of the plastic pieces for ulceration pad mounting.

Fasten ulceration pads onto the simulated foot using the plastic pieces. Add hot glue around the border of the opening for increased adherence (Appendices A-C).

Add black acrylic paint to the hallux to simulate the appearance of gangrenous and necrotizing tissue (Appendix C).

After debridement of necrotized tissue, replace the tissue with the addition of more super glue and dirt. Alternatively, remove the simulated ulceration entirely for replacement with another ulceration pad. Appendix A shows a fully debrided foot ulceration revealing healthy soft tissue.

Results

Using the above materials available in our simulation center, we created a simulator representative of a diabetic foot with debridable ulcers for an estimated cost of $71.28 USD. DFUs were made using suture pads, dirt, and super glue. For this model, wounds were localized on the dorsal aspect of the fourth and fifth metatarsals. On the plantar aspect of the foot, wounds were placed on the first metatarsal and calcaneus. This model design allows learners to practice the psychomotor skills associated with DFU wound debridement and wound dressing application. A photograph illustrating the use of the trainer for wound dressing can be seen in Appendix D.

Discussion

With the global prevalence of diabetes increasing at an alarming rate, diabetic neuropathy and foot ulcerations will likely increase (McDermott et al., 2022; Saeedi et al., 2019), underscoring the need for high-quality hands-on training. This task trainer was developed to support the goal of making more accessible training for managing DFUs. In addition to supporting the development of debridement and dressing techniques, the trainer can be modified to allow practice of other podiatric clinical skills. Because the resected regions are made from suture pads, they can be exchanged with pads containing premade lacerations and simulated debris for users to irrigate and suture. Incision and drainage of cutaneous abscesses on the foot can also be effectively simulated by incorporating lotion-filled balloons beneath suture pads (Adams et al., 2018; Freeman et al., 2014). Additionally, punch biopsies can also be performed by discoloring a small part of the suture pad with a marker to simulate an abnormal skin lesion. This model can also be used to train novice clinicians on wound assessment, classification, and sterile technique.

The net cost of the model components was $71.28 USD for one simulator. While the construction of the trainer is moderately priced, it was made utilizing resources that were readily available in our simulation lab. This cost can be mitigated by substituting comparable products from other manufacturers that offer lower-cost alternatives. Given the suture pads are one of the most costly components, we recommend reusing suture pads by creating new ulcerations each time. Plastic mannequin foot models can also be used as a substitute for more costly silicone foot models.

The hook-and-loop fastening mechanism allows for easy and rapid replacement of simulated DFUs for new users. Although this simulator was created for practicing DFU debridement and dressing application, the customizability of the design permits expansion to other procedural interventions. The detachable foot offers a customized experience, as it can be mounted and used independently or implemented into full-body manikin models for higher-fidelity simulation. Full body manikins may allow for a hybrid simulation for learners to develop interpersonal skills while performing the desired clinical procedures. This feature can be used to promote emotional engagement by allowing learners to respond to verbal expressions of pain from a simulated patient and to practice communication skills such as delivering bad news, including discussions about possible amputations (Ahmed et al., 2018; Brown & Reid, 2022; Brown & Tortorella, 2020). One limitation of implementing this design with full body mannequins is irreversible damage to the foot.

During the construction of this model, we encountered a logistical challenge. The original foot model was made of a stiff rubber material, which made it difficult to manually create wound beds suitable for debridement. As a result, the design team decided to completely resect parts of the rubber foot with a scalpel and to replace those parts with a softer suture pad. This was chosen over layering the pad on top of the original model because we believe filling the gap better simulates the level surface of a foot. Although layering the suture pad over the foot may not affect skill practice, the added elevation may compromise ergonomic and anatomic fidelity. Furthermore, the inserted pad provides a realistic simulation of a wound becoming progressively healthier as more necrotized tissue is debrided. For a more realistic and seamless experience, future upgrades to the current design may include using a foot model with a solid interior to limit cushioning when actively debriding.

Limitations of Design

Upon completion, we acknowledge several limitations present in the initial design of this simulator. First, based on the measured dimensions of our simulated task trainer the approximate shoe size for this trainer is a US men’s size 8. Mannequin models are generally limited to one size and cannot accurately reflect the varied shoe size and foot measurements amongst the general population. Implementing the DFU design methods into pediatric sized mannequins can allow specialists to practice debridement on a model foot with a much smaller surface area.

Next, because our model was hollow, we were required to pad the inside with foam for structural integrity and ulceration pad adherence. This mechanism of attachment may affect stability for steady debridement as there is no hard surface beneath the ulceration pad to secure the model in place effectively. Because of this, solid mannequin foot models may be recommended as a base for future designs. As the constructed DFU trainer is detached from a full body structure, it must be mounted to stabilize the model for practical use. This can be addressed by suspending the trainer to a comfortable height with the plantar side facing the user and utilizing clamps or ropes tied around the ankle joint to secure the model.

Lastly, subject matter expert opinions are vital to assess this model’s utility and efficiency. At the time of writing, we have not conducted any simulation sessions that incorporate this model into the educational curriculum. Usability testing of the model was conducted by simulation specialists at our academic institution. Although the simulator was not subjected to pilot testing following its development, its design and practical implementation were informed by the expertise of a board-certified physician with substantial experience in the clinical management of DFUs within emergency care settings. This physician provided guidance based on their knowledge of the clinical protocols and procedural nuances associated with debridement in patients presenting with ulcerations. Feedback regarding the practicality of using this simulator for debridement and other clinical skills should be gathered from podiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, physical therapists, and other wound care specialists who perform DFU debridement and podiatric care in routine clinical practice. In summary, given the numerous indications highlighting the potential of this design approach across various areas of simulation-based education, innovations in the present design and practical implementation of the model is essential to assess the usability of this simulator.

Conclusion

Using readily available items available in our simulation center, we created a task trainer that can serve as an efficient training modality for clinicians involved in providing podiatric care. Our model making methods allow for customizability in wound creation and distribution in trainers produced using these methods. As interactive podiatric simulators are expensive and can be difficult to acquire, we hope this conceptual design can contribute to increasing access to podiatry training and the development of more advanced simulators that can improve the management of patients with diabetic foot ulcers or other podiatric complications.

References

Adams, C. M., Nigrovic, L. E., Hayes, G., Weinstock, P. H., & Nagler, J. (2017). Teaching incision and drainage: Perceived educational value of abscess models. Pediatric Emergency Care, 34(3), 174-178. https://doi.org/10.1097/pec.0000000000001240

Ahmed, I., Amerjee, A., Akhtar, M., & Irfan, S. (2018). Hybrid simulation training: An effectiveteaching and learning modality for intrauterine contraceptive device insertion. Education for Health, 31(2), 119. https://doi.org/10.4103/efh.efh_357_17

Bader M. S. (2008). Diabetic foot infection. American Family Physician, 78(1), 71–79. PMID: 18649613

Bansal, V., Kalita, J., & Misra, U. K. (2006). Diabetic neuropathy. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 82(964), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2005.036137

Brown, W. J., & Tortorella, R. a. W. (2020). Hybrid medical simulation – a systematic literature review. Smart Learning Environments, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-020-00127-6

Brown, W. J., & Reid, C. (2022). Implementing a cost effective and configurable hybrid simulation platform in healthcare education, using wearable and web-based technologies. Smart Learning Environments, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00201-1

Diabetes Statistics. (2025, April 22). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/diabetes-statistics

Edmonds, M., Manu, C., & Vas, P. (2021). The current burden of diabetic foot disease. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma, 17, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcot.2021.01.017

Feldman, E. L., Callaghan, B. C., Pop-Busui, R., Zochodne, D. W., Wright, D. E., Bennett, D. L., Bril, V., Russell, J. W., & Viswanathan, V. (2019). Diabetic neuropathy. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0092-1

Frazee, B. W. (2024). Diabetic foot infections in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 42(2), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2024.01.003

Freeman, M., Wathen, P., Williams, J., & Zhang, M. (2014). Teaching incision and drainage of abscess. MedEdPORTAL. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9736

Grollo, A., Morphet, A., & Shields, N. (2018). Simulation improves podiatry student skills and confidence in conservative sharp debridement on feet. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association, 108(6), 466–471. https://doi.org/10.7547/16-121

IDF Diabetes Atlas. (2025, June 17). Copyright © IDF Diabetes Atlas 2024. All Rights Reserved. https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/idf-diabetes-atlas-2025/

Jeffcoate, W. J., & Harding, K. G. (2003). Diabetic foot ulcers. The Lancet, 361(9368), 1545–1551. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13169-8

Jeyaraman, K., Berhane, T., Hamilton, M., Chandra, A. P., & Falhammar, H. (2019). Mortality in patients with diabetic foot ulcer: a retrospective study of 513 cases from a single Centre in the Northern Territory of Australia. BMC Endocrine Disorders, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-018-0327-2

Jupiter, D. C., Thorud, J. C., Buckley, C. J., & Shibuya, N. (2015). The impact of foot ulceration and amputation on mortality in diabetic patients. I: From ulceration to death, a systematic review. International Wound Journal, 13(5), 892–903. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12404

Lebrun, E., Tomic-Canic, M., & Kirsner, R. S. (2010). The role of surgical debridement in healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 18(5), 433-438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475x.2010.00619.x

LeMaster, J. W., Mueller, M. J., Reiber, G. E., Mehr, D. R., Madsen, R. W., & Conn, V. S. (2008). Effect of Weight-Bearing Activity on Foot Ulcer incidence in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: Feet First randomized controlled trial. Physical Therapy, 88(11), 1385–1398. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20080019

Management-Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment (MND). (2016, October 21). Global report on diabetes: Executive Summary. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-nmh-nvi-16.3

McDermott, K., Fang, M., Boulton, A. J., Selvin, E., & Hicks, C. W. (2022). Etiology, epidemiology, and disparities in the burden of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care, 46(1), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci22-0043

Moura, L. I., Dias, A. M., Carvalho, E., & De Sousa, H. C. (2013). Recent advances on the development of wound dressings for diabetic foot ulcer treatment—A review. Acta Biomaterialia, 9(7), 7093–7114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2013.03.033

Ozougwu, J. C., Obimba, K. C., Belonwu, C. D., & Unakalamba, C. B. (2013). The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Physiol Pathophysiol, 4(4), 46-57. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPAP2013.0001

Rawshani, A., Rawshani, A., Franzén, S., Eliasson, B., Svensson, A., Miftaraj, M., McGuire, D. K., Sattar, N., Rosengren, A., & Gudbjörnsdottir, S. (2017). Mortality and cardiovascular disease in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine, 376(15), 1407–1418. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1608664

Saeedi, P., Petersohn, I., Salpea, P., Malanda, B., Karuranga, S., Unwin, N., Colagiuri, S., Guariguata, L., Motala, A. A., Ogurtsova, K., Shaw, J. E., Bright, D., & Williams, R. (2019). Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 157, 107843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107843

Snyder, R. J., & Hanft, J. R. (2009). Diabetic foot ulcers--effects on QOL, costs, and mortality and the role of standard wound care and advanced-care therapies. Ostomy/wound management, 55(11), 28-38. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19934461/

Ünlü, R. E., Orbay, H., Kerem, M., Esmer, A. F., Tüccar, E., & Şensöz, Ö. (2007). Innervation of three weight-bearing areas of the foot: An anatomic study and clinical

implications. Journal of Plastic Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery, 61(5), 557–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2007.02.007

Uppal, T. S., Chehal, P. K., Fernandes, G., Haw, J. S., Shah, M., Turbow, S., Rajpathak, S., Narayan, K. M. V., & Ali, M. K. (2022). Trends and Variations in Emergency Department Use Associated with Diabetes in the US by Sociodemographic Factors, 2008-2017. JAMA Network Open, 5(5), e2213867. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.13867