Authors

Alyssa R. Zweifel, RN, PhD, CHSE1, Phuong H. D. Nguyen, PhD2, Brittany A. Brennan, RN, PhD, CHSE, CNE1, & Michelle L. Lichtenberg RN, PhD1

1College of Nursing, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD

2College of Engineering, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest.

Corresponding Author

Alyssa R. Zweifel, RN, PhD, CHSE, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD

(Email: alyssa.zweifel@sdstate.edu)

Brief Description

This article explores the feasibility of integrating wearable physiological sensors into high-fidelity healthcare simulation to monitor cognitive load and fatigue. Using electrocardiogram (ECG) and galvanic skin response (GSR) sensors, we captured real-time physiological data from nursing students engaged in both virtual and manikin-based simulation scenarios. Signal processing confirmed data quality, and preliminary findings demonstrated that wearable physiological sensors can detect fluctuations in sympathetic nervous system activity related to task complexity and simulation demands. The results affirm the practicality of using wearable sensors in simulation operations and support their potential to enhance learner assessment, optimize scenario design, and advance research on stress and performance in healthcare education. This pilot project underscores wearable physiological sensors as a feasible and valuable tool for decoding human responses in complex training environments.

Introduction

Wearable physiological sensors, also known as biosensors, sense, detect, and transmit real-time physiological responses such as heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, movement, and cognitive load. This data can be used to diagnose, monitor, and manage health conditions (Zhang et al., 2025; Wang, 2024). Early research of wearable physiological sensors has predominantly focused on the clinical uses for patient monitoring, disease detection, and chronic disease management. Advances in wearable physiological sensors, such as smart contact lenses and sensor-embedded fabrics, will expand their capabilities, supporting new applications in educational settings and workforce monitoring (Risling, 2017).

Cognitive load, which is the mental effort required to process information, significantly affects a learner’s ability to acquire and apply knowledge in complex clinical scenarios (van Merriënboer & Sweller, 2005). The relationship between both subjective self-reported and objective measures of cognitive load, as well as the effects on clinical performance, remains inadequately explored in nursing education. Simulation-based learning is essential in nursing education, providing a safe environment for student development of clinical and decision-making skills without compromising patient safety (Lioce et al., 2020). However, during simulation-based learning experiences, the cognitive load for nurses can be overwhelming due to the complexity of the scenario, assigned tasks, and necessary clinical judgment (Rogers & Franklin, 2021). In the practice setting, mentally fatigued healthcare professionals experience cognitive overload, resulting in reduced attention, impaired decision-making, slower information processing, and increased distractibility (Karim et al., 2024). Furthermore, repeated and continuous exposure to mental fatigue increases the risk of medical errors and reduces overall quality of care (Dall’Ora et al., 2020; LeGal et al., 2019).

Cognitive load can be measured by assuming that changes in human cognitive functioning cause corresponding changes in human physiology, including heart rate and skin temperature (Larmuseau et al., 2019). Heart rate, as measured via an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG), can provide information about the overall function of the autonomic nervous system, specifically the effect of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system on heart rate (Tiwari, et al., 2021). As cognitive demand increases in individuals, heart rate increases (Grassman et al., 2017).

The Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) measures skin conductance using sensor electrodes placed on the skin. Changes in conductance reflect variations in skin moisture, which are influenced by fluctuations in sympathetic nervous system activity (Larmuseau, et al., 2019). As an individual experiences more or less stress, the GSR increases or decreases, respectively (Hoogerheide, et al., 2018; Smets et al., 2018). Additionally, previous research indicates that increased cognitive load is associated with heightened GSR responses (Nourbakhs et al., 2012; Yousoof & Sapiyan, 2013).

Recent research has explored the physiological signs of distress in healthcare professionals, offering insights into the causes of burnout and other issues affecting well-being (Barac et al., 2024). Despite mitigation efforts by healthcare organizations, over half of U.S. nurses reported burnout symptoms in a 2023 survey (Berlin et al., 2023). A significant opportunity exists to explore how wearable physiological sensor technology can specifically benefit healthcare professional students. By deepening the understanding of student well-being throughout their educational programs, assessments can be enhanced, clinical performance improved, and awareness of physiological and psychological stress responses increased. Furthermore, by quantifying and analyzing stress levels among healthcare students during their training, effective strategies to alleviate stress can be developed and implemented. This proactive approach not only protects students’ well-being but also prepares them to provide safe, high-quality care in the healthcare field.

Methods

This pilot study explores the implementation of wearable physiological sensors to assess and enhance participant performance in simulation-based training environments, with a primary focus on fatigue and cognitive load. By monitoring real-time physiological indicators such as heart rate variability and electrodermal activity, we evaluated the feasibility and value of wearable physiological sensors in understanding human responses during complex, high-stakes simulation scenarios.

Sample and Setting

The study participants (n=6) were full-time senior level nursing students at a Midwestern undergraduate baccalaureate program in the United States. The setting was a Society for Simulation in Healthcare (SSH) accredited simulation center that runs high-fidelity, simulation-based learning. The center is staffed by experienced Certified Healthcare Simulation Educators (CHSE) and follows the Healthcare Simulation Standards of Best Practice®, ensuring realistic scenarios and a safe learning environment.

Data Collection

The participants were equipped with both GSR and ECG sensors during the simulation activities. The Shimmer3 GSR and Shimmer3 ECG units provided a configurable digital front-end, optimized for measuring physiological signals related to skin temperature and heart rate, respectively.

All six participants attended a pre-briefing, followed by time to connect the wearable physiological sensors before participating in the simulation-based learning scenario with standard debriefing utilizing the PEARLS Debriefing Framework. Two of the participants were completed an immersive virtual reality (VR) simulation learning scenario. In this scenario, learners assumed the role of a primary nurse caring for a 9-year-old client presenting to the emergency department (ED) with new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus, requiring assessment, communication, and clinical decision-making. The remaining four participants completed a high-fidelity manikin-based complex scenario, which cared for a 64-year-old client in the ED suffering from cardiac arrest. Primary and secondary nurses are required to work within the interprofessional team completing quick assessments, interventions of high-quality CPR and emergency medication, and effective team communication.

Data Processing and Analysis

The raw sensing signals often contain noise and artifacts from movement, electrode displacement, and external electrical interference. The collected ECG and GSR signals were processed, which included filtering techniques such as low-pass and high-pass filters to eliminate irrelevant frequencies to remove noise and artifacts. Additionally, notch filters were used to eliminate power line interference at 50 Hz for each sensing signal region. The data analysis was performed using iMotions Lab, a modular software for capturing, processing, and analyzing physiological sensors with built-in R Notebooks.

The physiological responses of the participant during the VR simulation were also measured using the HRV measured using the Standard Deviation of NN Intervals (SDNN) and inter-beat interval (IBI) distributions. SDNN is a measure of HRV that calculates the average value of HRV in milliseconds, reflecting the time between heartbeats. IBI is a measure of heart rate signals, which is used to assess the health of the participant’s autonomous nervous system during the simulation process.

For example, increases in heart rate (shorter inter‑beat intervals) coupled with decreases in heart rate variability, particularly lower SDNN, indicate a shift toward sympathetic dominance and reduced vagal modulation as the autonomic nervous system mobilizes resources for demanding mental activity. In parallel, increases in skin conductance level and the frequency/amplitude of phasic responses reflect activation of eccrine sweat glands under purely sympathetic control, providing a direct index of arousal and attentional engagement. Taken together, the pattern of higher heart rate, lower HRV, and higher skin conductance during task periods is a signature of elevated cognitive load. When sustained, these sympathetic‑based responses can be interpreted as accumulated cognitive fatigue, with the prolonged effort leading to delayed parasympathetic recovery and reduced variability during and after task blocks.

Results

The signal processing results show that the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the collected sensing data was above 28.48 dB, indicating excellent quality of the signal, with less than 1% noise. The following preliminary results suggest that GSR and ECG measurements reflect the participants’ fatigue levels and the patterns of their cognitive load during simulation.

Heart Rate and Skin Conductance during Simulation Scenarios

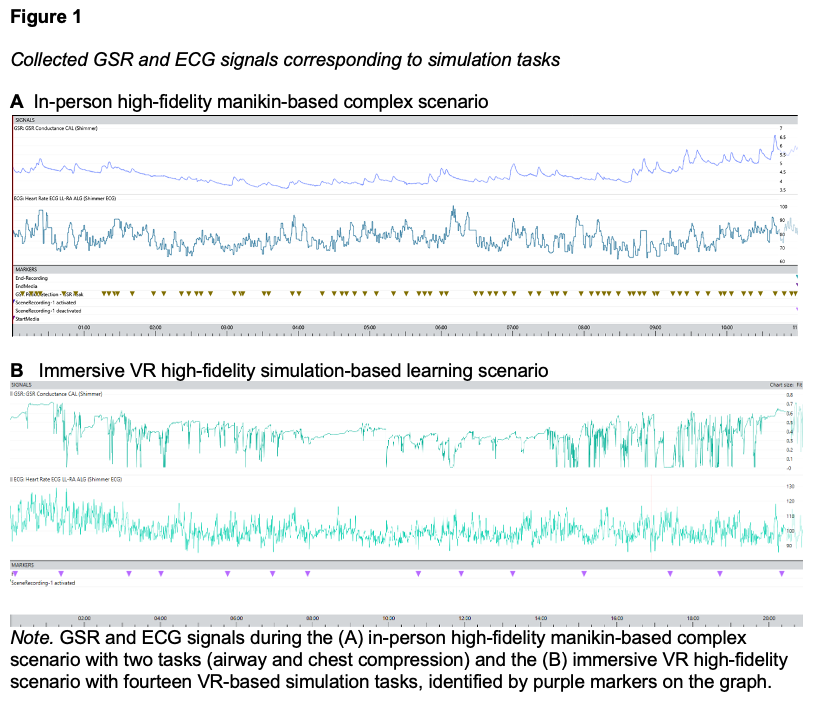

The ECG and GSR data from the two simulations is shown in Figure 1. For the high-fidelity manikin-based scenario, participants completed two tasks (airway and chest compressions) over 10 minutes (Figure 1A). For the immersive VR simulation, participants completed 14 tasks over 20 minutes (Figure 1B).

The GSR conductance fluctuates significantly over the course of the immersive VR scenario (Figure 1B), ranging approximately from 0.1 to 0.7 micro siemens (µS), representing the sympathetic nervous system activation associated with the participant’s cognitive load during the simulation process. A particularly noticeable increase in variability is observed in the second half of the scenario, corresponding to elevated physiological fatigue of the participant. The ECG data demonstrates a similar variation in heart rate, indicating changes in the participant’s physiological state, including arousal, fatigue, and relaxation. There are several periods of increased heart rate when changing tasks within the simulation, suggesting an increased cognitive load. GSR peaks frequently coincide with increases in heart rate because both are markers of sympathetic activation during cognitively demanding tasks, but their relationship is not one-to-one. Unlike GSR, which reflects purely sympathetic input, heart rate is jointly regulated by sympathetic and parasympathetic influences; as a result, heart rate may not consistently increase even when a GSR peak occurs.

Figure 1 also shows the recovery periods where both signals stabilize, reflecting a return to baseline arousal levels when the simulation was completed. As a result, both the ECG and GSR signals demonstrate prominent peaks and high variability in two phases: (1) at the start of the simulation associated with an increased cognitive load and (2) towards the end of the simulation associated with an increased fatigue level.

Figure 2 also shows patterns of heart rate and skin conductance during both the simulation scenarios. Figure 2B shows the participant’s heart rates are on a fast-pace and more intense during the immersive VR cardiac arrest activity, oscillating frequently between 60 and 90 beats per minute. This suggests a dynamic physiological process linked to the physical activities during the VR-based simulation. In the first part of the VR session, around the first 100 seconds, the heart appears more erratic as the participant started the simulation. High HRV often indicates adaptability and a healthy stress-response system when it correlates with mindfulness activities. A few sharp peaks and dips indicate several simulation tasks (e.g., during the 350-390s) affecting the heart rate. The graph's lowest values hover around 60 bpm, indicating the participant’s resting heart rate after a high cognitive load period.

Figure 2B shows the GSR data during the immersive VR cardiac arrest simulation activity. The GSR values range from 3.6 μS to 6.6 μS, indicating significant changes in skin conductance, driven by the participant’s physiological responses to the VR simulation tasks. In the initial phase (0–200s), a declining trend in GSR was observed, indicating a reduction in stress levels as the participant was going through the VR-simulation tasks. In the middle phase (200–400s), the GSR showed frequently moderate fluctuations with small peaks, suggesting short-term changes during the simulation tasks. In the final phase (400–600s), a steady increase in baseline GSR occurred with larger and more frequent peaks, indicative of heightened engagement of the participant due to increasing task demands. This suggests a sustained increase in sympathetic nervous system activation due to the participant’s prolonged focus on the simulation tasks. Also in this phase, responses appeared longer and more sustained, reflecting a shift in the participant’s emotional state. Peaks in the later phase were more frequent and larger in amplitude, indicating increased physiological response to the simulation tasks.

Figure 2B also demonstrates the relationship between heart rate and GSR. During periods of rising heart rate corresponded to increase in GSR peaks, suggesting synchronized physiological responses of the participant to changes in the simulation tasks. After 200 seconds, both metrics show an upward trend, suggesting the increase in task complexity was leading to higher fatigue levels of the participant. Also in the first half, there were frequent heart and GSR fluctuations, indicating periods of heightened cognitive demand. Eventually, around the midpoint of the simulation, heart rate stabilized and GSR baseline decreased, suggesting reduced cognitive engagement.

Heart Rate Variability during Simulation Scenarios

The physiological responses of the participant during the VR simulation were also measured with HRV, specifically, using the Standard Deviation of NN Intervals (SDNN) and inter-beat interval (IBI) distributions. SDNN is a measure of HRV that calculates the average value of HRV in milliseconds, reflecting the time between heartbeats. IBI is a measure of heart rate signals, which is used to assess the health of the participant’s autonomous nervous system during the simulation process.

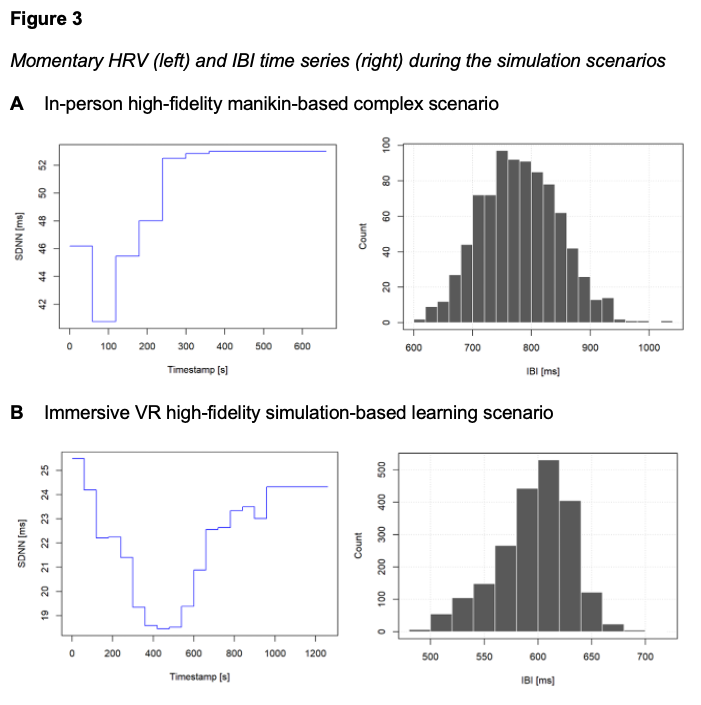

Figure 3 shows two aspects of HRV analysis, SDNN over time (left) and IBI distribution (right). During the manikin-based complex scenario (Figure 3A), the SDNN immediately declines, reflecting an increased cognitive load at the beginning of the simulation. In contrast, during the immersive VR scenario (Figure 3B), SDNN declines more gradually from 25ms to a low of 19ms by approximately 400 seconds. This decrease in SDNN at the beginning of the simulation indicates heightened sympathetic activity as a result of the increased task demand and cognitive load. After this midpoint, SDNN steadily rises, returning near its initial value (24ms) by 1200 seconds. This suggests physiological recovery and relaxation as the scenario progresses. Both scenarios demonstrated this overall U-shaped pattern, reflecting an early increase in cognitive load, followed by mid-task fatigue, and subsequent recovery at the end of the simulation.

For the manikin-based activity, Figure 3A also shows that the most frequent IBI value is around 750 – 800 ms, with a high concentration of beats in this interval. Figure 3B, which represents the immersive VR scenario, shows the most common IBI value is around 600 ms. Overall, for the VR scenario, the histogram demonstrates a relatively consistent heart rhythm with only minor variations between beats. The standard deviation of the IBI data (20.27 ms) indicates relatively stable beat-to-beat variability, consistent with a moderate workload throughout the simulation for the participant. The total IBI range of 116.14 ms reflects some variability in heart rate, suggesting brief transitions between cognitive load and fatigue. Taken together, the distribution reflects overall low-to-moderate HRV, indicating (1) a generally steady rhythm during the activity and (2) reduced physiological adaptability as the participant engages in various, changing simulation tasks.

Discussion

Understanding how nurses and other healthcare professionals react during stressful patient care situations where a high cognitive load can lead to fatigue, may help explain the healthcare professionals’ burnout and cognitive overload. Physiological indicators of distress in healthcare professionals may offer insights into the causes of burnout and other issues affecting well-being and patient safety risks.

Reviewing wearable physiological sensors data, we identified several periods of higher heart rate correlating with changing simulation tasks, indicating an increased cognitive load. Similarly, increased GSR peaks corresponded with higher heart rate activity, suggesting a synchronized response to the participant’s task demands. Both the heart rate and GSR data demonstrate prominent peaks at the start of the simulation scenario and toward the end of the scenario. This can be associated with an increase in cognitive load and changes in physiological states, leading to higher fatigue levels.

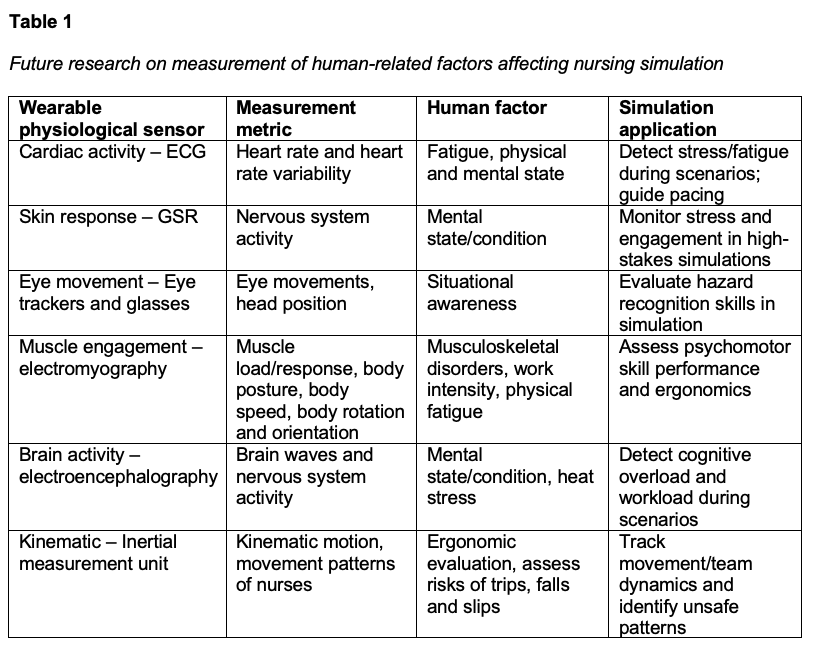

These results suggest wearable physiological sensors are feasible and valuable in healthcare settings, as they were able to capture meaningful physiological responses, including increased sympathetic activity associated with higher task demand and cognitive load during the simulation. Future healthcare simulation studies with larger sample sizes are needed to better understand the correlation to specific patient care situations. Additional research may compare virtual reality and manikin-based modalities to determine whether one modality better captures patterns of cognitive load and fatigue, as well as extend monitoring into the debriefing phase where much of the learning occurs. Future investigations should also continue to integrate and compare biosensor data with participants’ self-reported cognitive load and fatigue, an area our team is already actively examining. Table 1 shows future research directions of this study by implementing a multi-sensory system with ECG, GSR, eye-trackers, EMG, EEG, and IMU.

Limitations of Design

The limitations of this pilot study include a small sample size and no direct comparison between the two modalities of simulation-based education (manikin-based and immersive VR). The study results also lack a comparison of biosensor data with participants’ self-reported perceptions of fatigue and cognitive load, which would bring an important step towards advancing this research. Integrating self-report measures alongside sensor data could examine alignment and discrepancies between subjective and objective measures, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the learner experience.

Conclusion

This study explores the implementation of wearable physiological sensor technologies to assess participant performance in high-fidelity simulation-based training environments, with a primary focus on fatigue and cognitive load. From a successful pilot using GSR and ECG sensors to monitor real-time physiological indicators of cognitive load, we found that wearable sensors are both feasible and valuable for assessing human responses during simulation-based learning activities. Our research suggests increased sympathetic nervous system activity associated with elevated task demand and cognitive load can be reliably captured through these wearable sensors. We further highlight the applicability of physiological sensors use, drawing parallels between healthcare simulation and the patient care setting where situational awareness and cognitive load are equally critical. These findings support using wearable physiological sensors as a practical tool for providing insight into participants’ cognitive load and fatigue during training, which can enable more effective assessment, feedback and learning in healthcare simulations, with the goal to improve patient safety.

References

Barac, M., Scaletty, S., Hassett, L. C., Stillwell, A., Croarkin, P. E., Chauhan, M., Chesak, S., Bobo, W. V., Athreya, A. P., & Dyrbye, L. N. (2024). Wearable technologies for detecting burnout and well-being in health care professionals: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 26, e50253. https://doi.org/10.2196/50253

Berlin, G., Burns, F., Hanley, A., Herbig, B., Judge, K., & Murphy, M. (2023). Understanding and prioritizing nurses’ mental health and well-being. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare/our-insights/understanding-and-prioritizing-nurses-mental-health-and-well-being#/

Dall’Ora, C., Ball, J., Reinius, M., & Griffiths, P. (2020). Burnout in nursing: A theoretical review. Human Resources for Health, 18(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9

Grassmann, M., Vlemincx, E., von Leupoldt, A., & Van den Bergh, O. (2017). Individual differences in cardiorespiratory measures of mental workload: An investigation of negative affectivity and cognitive avoidant coping in pilot candidates. Applied Ergonomics, 59(A), 274-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2016.09.006

Hoogerheide, V., Renkl, A., Fiorella, L., Paas, F., & van Gog, T. (2018). Enhancing example-based learning: Teaching on video increases arousal and improves problem-solving performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 211. 45-56. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000272

Karim, E., Pavel, H. R., Nikanfar, S., Hebri, A., Roy, A., Nambiappan, H. R., Jaiswal, A., Wylie, G. R., & Makedon, F. (2024). Examining the landscape of cognitive fatigue detection: A comprehensive survey. Technologies, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies12030038

Larmuseau, C., Vanneste, P., Cornelis, J., Desmet, P., & Depaepe, F. (2019). Combining physiological data and subjective measurements to investigate cognitive load during complex learning. Frontline Learning Research, 7(2), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v7i2.403

LeGal, P., Rheaume, A., & Mullen, J. (2019). The long-term effects of psychological demands on chronic fatigue. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(8):1673-1681. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12857

Lioce, L. (Ed.), Anderson, M., Diaz, D., Robertson, J., Chang, T., Downing, D., Spain, A. (Associate Eds.), & Terminology and Concepts Working Group. (2020). Healthcare Simulation Dictionary (2nd ed.). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://doi.org/10.23970/simulationv2

Nourbakhsh, N., Wang, Y., Chen, F., & Calvo, R. a. (2012). Using galvanic skin response for cognitive load measurement in arithmetic and reading tasks. Proceedings of the 24th Conference on Australian Computer-Human Interaction OzCHI ’12 https://doi.org/10.1145/2414536.2414602

Risling, T. (2017). Educating the nurses of 2025: Technology trends of the next decade. Nurse Education in Practice, 22, 89–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2016.12.007

Rogers, B., & Franklin, A. (2021). Cognitive load experienced by nurses in simulation-based learning experiences: An integrative review. Nurse Education Today, 99, 104815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104815

Tiwari, R., Kumar, R., Malik, S., Raj, T., & Kumar, P. (2021). Analysis of heart rate variability and implication of different factors on heart rate variability. Current Cardiology Reviews, 17(5), 74-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1573403X16999201231203854

van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Sweller, J. (2005). Cognitive load theory and complex learning: Recent developments and future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-005-3951-0

Wang, Y.-H. (2024). Exploring technology-driven technology roadmaps (TRM) for wearable biosensors in healthcare. IRBM, 45(3), 100835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irbm.2024.100835

Yousoof, M., & Sapiyan, M. (2013). Measuring cognitive load for visualizations in learning computer programming-physiological measures. Ubiquitous and Communication Journal, 8. 1410-1426.

Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Yin, Z., Huang, L., & Wang, J. (2025). Nanozyme-based wearable biosensors for application in healthcare. IScience, 28(2), 111763–111763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2025.111763